One of the consistent themes in reading anything about the U.S. employment market is the massive income premium afforded to college graduates vs. those with no degrees. One of the other consistent themes is the increasingly large debt load of college students, debts which can't be discharged in bankruptcy.

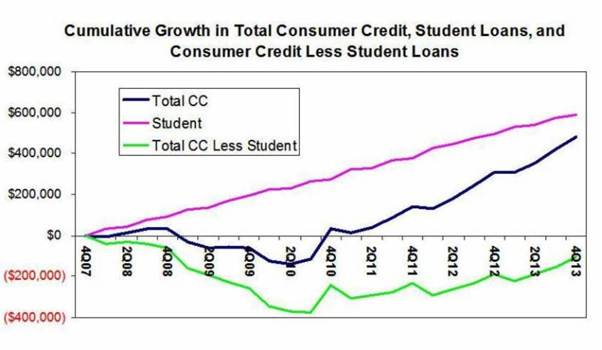

The debts pile up for a lot of graduates, ones who can't repay it on the job market. The graph below illustrates the relative increase in recent years, in part driven by ever-increasing tuition loads.

That always gets me interested in figuring out a way to short student loans and betting on default - but I don't think there's a way to do it. However, it also gets me interested in alternative tuition models - and one that I've read about a number of times is a repayment plan based on future earnings rather than fixed debt payments.

From a Vox.com summary

Right now, in-state tuition at the University of Oregon is around $10,000 per year. Students can pay that up front with their own money or with grants and scholarships. Or they can take out a loan from the US Education Department and pay it back after they graduate. Once they've paid back the amount they borrowed, plus interest, they're done, whether that takes 10 years on a standard plan or longer on an income-based plan.

But Oregon is also exploring another model, where students wouldn't have to pay tuition at all when they enroll. Instead, they'd pay 3 percent of their income to the state for 20 years after graduation.

Essentially, Oregon could get rid of public college tuition and replace it with a flat tax on graduates' incomes.

Sounds like an interesting idea - and this article (along with others that describe similar systems) talk a lot about the burden it removes from emerging graduates.

But there's an aspect that consistently goes unmentioned, and something that I think would be a huge argument for the model, and that's the impact it would have on the universities themselves.

I don't mean an impact on tuition loads. This type of scheme doesn't seem to do anything to curb tuition inflation generally. But what I have to assume it would change is the focus and emphasis colleges place on employer relations and career services.

When I was at Penn State (seemingly forever ago) - the career services department's help was - let's say - limited. I remember a couple career fairs at the basketball stadium, I remember applying through on-campus recruiting, and I remember it was around 2002, so employers would show up and tell you they didn't have any immediate openings but they'd be sure to get back to you in the future.

Although I really didn't know it at the time, I should've been a little disappointed in the level of service (or maybe I should've been a little more proactive...probably both).

But now let's assume that Penn State wasn't getting a check from my family every semester, but instead, it was effectively investing in my FUTURE earnings on a payback scheme. Now the incentives have changed, and the school will care a whole lot more not just about whether I get a job, but whether I get a job that pays me very well.

Now some would argue that schools have all the incentive in the world to make sure their students get jobs. You could argue it helps their rankings (which I believe has a component based on employment rate...at least MBA programs are evaluated that way). But that type of metric (percent of students employed) is a binary one which doesn't get to quality of employment (someone with a job at McDonald's would count the same as a Fortune 500 CEO - which would be a hell of a job out of undergrad).

But if the school's financial interest rests on helping students find high paying jobs - then I have to assume they'll care a lot more about getting the best recruiters to campus and preparing their students to out-compete their peers at other schools. The ROI on those efforts, all of sudden, would really matter - today you could argue they try to create successful alumni to donate, but as far as I'm concerned that's not even in the same ballpark as a defined financial arrangement based on graduate compensation.

It would get the schools a lot more invested in getting students employed, and employed meaningfully. It should (my thinking goes) also work to reallocate university investment in programs which create the types of employees companies are looking for (e.g., business, not basket weaving). So when it comes time to hire faculty, build new facilities, or establish new programs, the school might think about how much more employable the students will become.

The argument against this would be that universities should serve to advance the interests in all fields, and not just ones which churn out accountants and computer science majors and doctors - but also, I don't know, philosophers or something.

Meh - call me a heartless pragmatist.

No comments:

Post a Comment